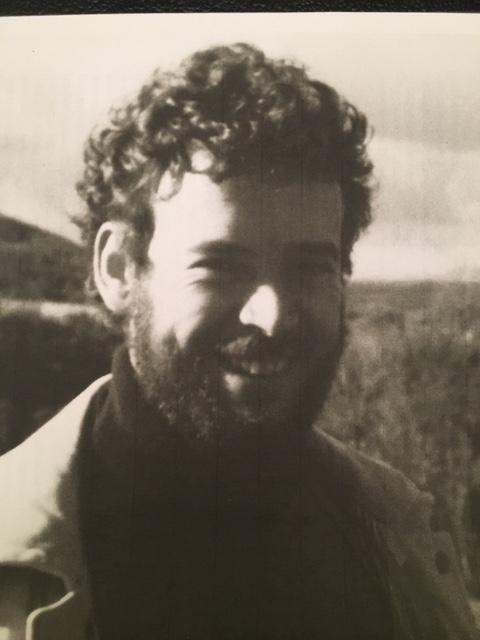

In May 1979 a brutal car accident put an end to the life and work of

Jean-Louis Robert. There remains, however, the ever-vital memory of his

eminently warm influence, vibrant with a passion for discovery,

assimilation, transmission and communication through music, together

with his fervent desire to bring us closer to a more convivial society,

one that is respectful of all and based on genuine human relationships,

such as is reflected in the sparkling diversity of his output, teeming

as it does with beautiful sounds, with overwhelming emotion and density.

This is a voice of supreme independence and freedom, indebted to no

school, system or fashion, and this is where his significance lies, as

well as his eternal relevance, happily attested to by a few recordings.

Born near Haine-Saint-Pierre in 1948, Jean-Louis Robert was a pianist, a

composer, a teacher (at the "Académie de Nivelles"; in the workshops of

the "Centre de Recherches" and the Liège Conservatory; at the music

school of Grez-Doiceau - where his position as director enabled him to

give free rein to his pedagogical ideas) and also organiser (in the

"Centre Culturel du Hainaut"; for the "Jeunesses Musicales" in Nivelles;

at the "Centre de Formation d'Animateurs Musicaux" - Cefcam - that he

had founded in Nivelles). He realised very early on that composition

would be his way. In 1967 he attended a concert of the "Ensemble

Musiques Nouvelles", presented and directed by Pierre Bartholomée, a

concert that included a work by Henri Pousseur. It was a revelation and a

turning-point. In October 1971 he enrolled in Pousseur's composition

class in the Liège Conservatory. There was instant osmosis between these

two men, brought together by many ideas - utopian society, absence of

ostracism towards any musical genre, performer or audience -, yet this

identity of views never made Jean-Louis Robert an imitator of Pousseur.

Their relationship was always, as Philippe Perreaux has emphasised in

his study of the composer, of the same order as that between Webern and

Schönberg. He was a passionate lover of Sibelius's and Mahler's music -

to which his own has often been compared, he was fascinated by the

repetitiveness of Steve Reich, and was a discerning connoisseur of

Messiaen's language, of which he admitted the influence on his own music

(especially in the use of percussion and keyboard instruments). He also

admired Cage's approach and Varèse's style (a direct influence of which

can be seen in the alternation of oboe and orchestra at the start of

Aquatilis). He discovered, with Icare obstiné, the technique of

networking, by which Pousseur reintroduced harmonic colour into music

without renouncing the acquisitions of serialism, a feature lying atthe

heart of most of his works. It was here also that he increased his

knowledge by taking an active and enthusiastic role in the detailed

analysis of twentieth-century scores, in particular of Stravinsky,

Webern, Stockhausen, Berio, and of earlier masterpieces such as the

Dichterliebe, from which Pousseur drew the essence of his book Schumann,

le poète and its musical pendent Dichterliebesreigentraum (CD Cyprès

CYP7602). In April 1973 the class took part in a national weekend of the

"À Cur Joie" choirs, focusing on the song Le Temps des Cerises and on

its potential for elaboration, for which Jean-Louis Robert composed an

intermezzo, Le Cerisier éclaté, a large-scale mobile and "one of the

most beautiful piano pieces for many a year" (Henri Pousseur). In June

1976 he took part for the first time as pianist in a concert of the

"Ensemble Musiques Nouvelles", and from then on a number of his scores

were written for the soloists of that group.

His first extant work, Instant for piano, dates from before the

seventies, and was followed, in 1971, by two pieces for voice and piano,

Au bord du lac and Chao-Chun. From then on, in addition to some

orchestrations prepared for Pousseur (4e Vue sur les jardins interdits

in 1974, Parade de Votre Faust in 1975), his output was enriched with an

impressive number of works: Icare obstiné Vol III for piano, first

performed by Marcelle Mercenier at Saint Hubert in July 1972, Le Coin

d'Icare, eleven teaching pieces for piano "their inspiration stemming

from Debussy and Webern"), D'Icare à Liège, three pieces for piano,

Conte de veillée de Nouvel An for piano. In 1973 there followed Le

Cerisier éclaté for piano, L'Arbre sans ombre, a setting of three short

texts by Michel Butor for baritone and orchestra, Clav Icar, a "game to

stimulate improvisation" for any keyboard instrument and for at least

two players. In 1974 he composed: Le Silence du Micocoulier for flute

and guitar; in 1975: Le Jardin des Cercles for tcheng, written at the

request of Andrée Van Belle and composed in the style of a minimalist

piece by Cage, Ascèse de Traversée for clarinet, piano and double bass,

which was to be "the source of other [works]: the beginning and the

conclusion, in particular, were re-used in Lithoïde VIII, and the idea

of starting in the prolongation of a chord was taken up in Aquatilis"

(Philippe Perreaux), L'Arbre des Sources, a work in four sections for

instrumental ensemble, dedicated to Pierre Bartholomée and written for

the event of the same name organised by Robert in Nivelles; L'Arbre des

Utopies déchiffrées for various ensembles and choirs, dedicated to Henri

Pousseur, in which are quoted, in a very successfully integrated

manner, works and styles of particular composers: Debussy, Stravinsky,

Varèse, Pousseur, Webern, Xenakis, Bartholomée, Boesmans; Le Verger

perdu, a work in three parts for mixed chorus or mixed chorus and

instruments, Antigone for small ensemble and unison male chorus,

L'Horizon des Eaux for amplified clavichord and instrumental ensemble (a

homage to Pierre Bartholomée, whose "poetic rigour" Robert Liked, the

work quoting rhythmic figures from Fancy), Miroir des Sources, a very

Mahlerian piece for string orchestra; in 1976: Lithoïde I, II, III and

IV, all for indeterminate ensemble, except for the second, written for

three unspecified instruments or for horn, trumpet in C and trombone,

Calycanthe, a tape piece based on a mix of his own works, Lithoïde V for

cello; in 1977: Lithoïde VI for violin, VII for organ and trumpet,

Aquatilis for orchestra "a summing-up work" (Philippe Perreaux) written

at the request of Pierre Bartholomée to inaugurate his new policy of

first performances by the "Orchestre Philharmonique de Liège", Lithoïde

VIII for brass quintet; in 1978: Domino for percussion and piano or two

non-specified instrumental ensembles, Milarepa for four percussionists

and tcheng or any instrumental ensemble; in 1979: Takshasilâ I for

clarinet, Lithoïde IX, a large-scale mobile for oboe, which was left

unfinished at his death.

Written within a brilliantly assimilated and ever-living tradition, the

works of Jean-Louis Robert all seek to establish a new relationship

between the composer, the composition and the performer. To mention only

those works on the present CD, Aquatilis offers the orchestra a maximum

of independence as it starts and finishes without the conductor,

Lithoïde VIII allows the performers to choose the tempi, and Domino is

mainly based on improvisation.